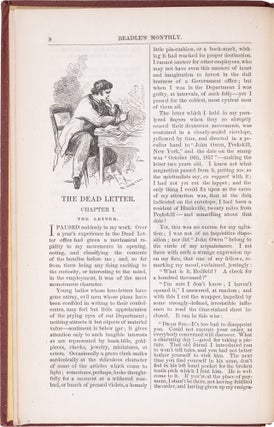

The Dead Letter

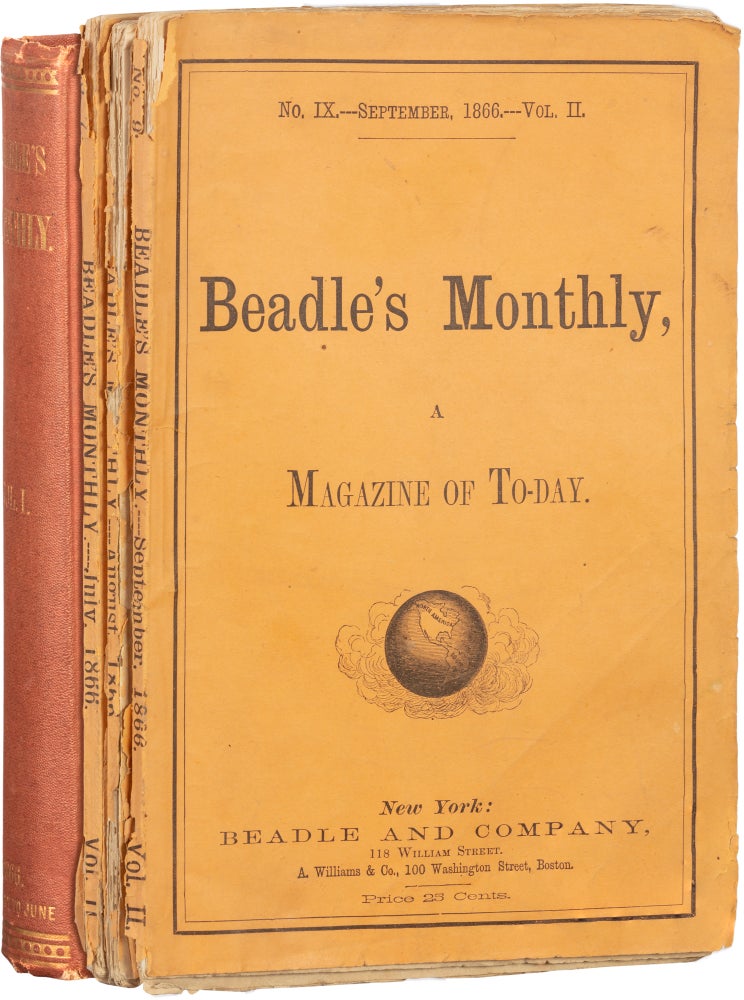

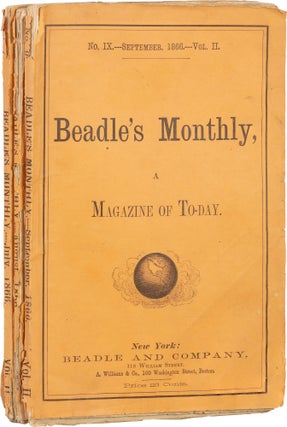

New York: Beadle’s Magazine, 1866. First Edition. mixed. 1st edition in 9 parts as issued. A posited 1864 edition is a chimera, reports of it stir needless uncertainty, all serializations with dates after 1866 are reprints, and all spellings of the author’s pen name as “Register” are careless mistakes. Depending on how one defines “detective novel” The Dead Letter is arguably the first one by anybody anywhere, it is certainly the first detective novel written by a woman irrespective of how detective is defined, and it’s the first by an American of either gender. Parts 1–6 (Jan.–June) are together in their original copper colored cloth, as issued, the only publisher’s hardcover binding, 3 tiny dents to the front cover, a few rubs, and a small inscription, else near fine, fresh, unrepaired, and unexpectedly well preserved, and copies in leather, or any other cloth, are all rebound regardless of how they’re described or what they are called. Parts 7–9 (Jul.–Sept.) are in their individual, original (publisher’s), paper wrappers. All 3 have tears to their edges, the Aug. wrapper with a 1 1/2” chip, and the other 2 with smaller chips, else good, sound, integral and complete. All 9 vols. in a fine half morocco case. Rare like this, on the outskirts of probability, and even rebound copies are not common. Very good. Item #488

Using the very loosest definition of documented detective narratives, they trace back to Sophocles’ play Oedipus Rex (430 BC). More modern materializations as short stories, having some of the markers but lacking some too, include The Three Apples in The Arabian Nights (ca. 1000 AD), Voltaire’s Zadig (1748), Hofmann’s Das Fräulein von Scuderi (Miss de Scuderi, 1819), and Burton’s The Secret Cell (1837). Unquestioned as detective stories are Poe’s The Murders in the Rue Morgue (1841), The Mystery of Marie Roget (1843), Thou Art the Man! (1844), and The Purloined Letter (1845). Novels are a more modern, but inevitable, invention and both Zadig and Miss de Scuderi can be ignored as only long enough to qualify as novellas. The first real novel with an all–knowing narrator was Fielding’s Tom Jones (1749), but the only parts of it harkening detective fiction are the mystery surrounding Tom’s birth and Fielding’s liberal use of misdirection. The Gothic novel (tracing to the 1760s always had a mystery, and usually a crime, but not a real detective. Hansen’s The Murder of Engine Maker Roolfson (1839) is indeed a crime novel but it also lacks a professional, or even an amateur detective (an assessor plays the role). Alexandre Dumas read Poe, recognized it immediately and wrote Une Fille du Régent (The Regent’s Daughter, 1844). It’s a detective novel in all ways. The crime is a planned assassination, and the clues that lead to its uncovering are clearly and logically presented, but fans nitpick it because the detective is Cardinal Dubois, a court politician draped in red, not a private eye or the police. The fans are wrong. The honor, practicably, belongs to Dumas, but we’ll pass him by for now. From there, Dickens’ Bleak House (1853) has a Scotland Yard police inspector but he is mostly confined to a subplot. Collins The Woman in White (1860) qualifies, with the only complaint against it (like with The Regent’s Daughter) being that amateurs do the detecting (the victim’s half sister, assisted by her drawing teacher). Hugo’s Les Miserables (1862) has a Paris police detective, and he plays the most prominent of roles, but the only mystery is whether Valjean will be caught. Charles Felix’s (pen name of Charles Adams) The Notting Hill Mystery (1863) has its detecting done by an insurance company investigator (like in Cain’s Double Indemnity), and though it has all the other pieces in place, the pieces aren’t very good. And then there is Metta Victor’s (as Seeley Regester) The Dead Letter (1866) with its Mr. Burton, a working private detective. It’s followed by a different twist in both Dostoyevsky’s H (Crime and Punishment, 1866) and Zola’s Thérèse Raquin (1867), then twisted back to the straighter path in Gaboriau’s Monsieur Lecoq (1868), and Collins’ The Moonstone (1869), wherein the type was perfected. I’ll also mention Green’s The Leavenworth Case (1878) and call it no more than an overly acknowledged late arrival, and the mother of nothing. And certainly the plotlines, and the detective himself, or herself, were improved upon delightfully, in cycles over the next 150 years, from Doyle’s Holmes (1887), Christie’s Poirot (1920) and Marple (1927), Hammett’s Continental Op (1923) and Sam Spade (1929), Chandler’s Marlowe (1939), Kane’s (and Finger’s) Batman (1939), and even to Ruby and Spears’ Scooby Doo (1969), and Butcher’s Harry Dresden (2000). Metta Victor was an incredible woman and a titanic literary figure. Beyond her place in the detective fiction hierarchy, she inaugurated an industry, writing the first original “Dime Novel” (Alice Wilde) in 1860. It was part of what became a 321 book series called “Beadle’s Dime Novels” that sold 5 million copies. The first Beadle Dime Novel (number 1) was Stephens’ Malaeska, The Indian Wife of the White Hunter (1860), but it was not an original Dime Novel, being a reprint of its 1839 1st edition, while Metta Victor’s Alice Wilde was written for Beadle by design, and its publication in the Dime Novel series (also 1860) was its 1st edition. Beadle’s template activated a rise in U. S. literacy and spread to dozens of publishers (Victor wrote 100 of them). The aim was to astonish readers rather than oblige critics, and while exact total figures are unsure, The University of Minnesota claims to have a collection of 65,000 titles.

Price:

$7,500.00