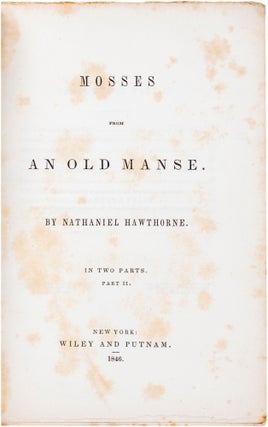

Mosses from an Old Manse

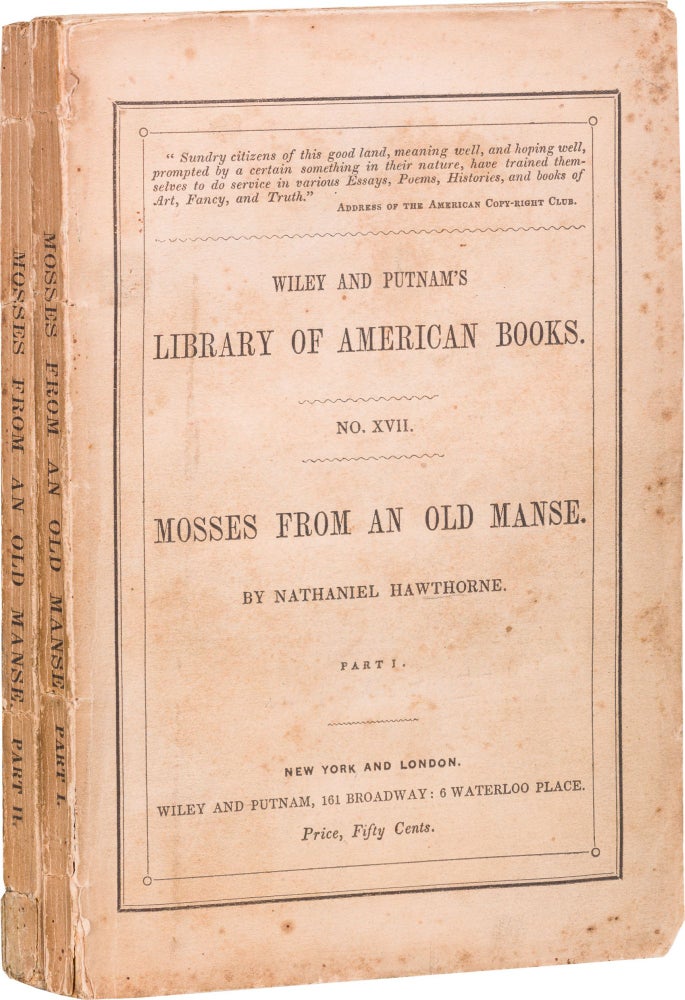

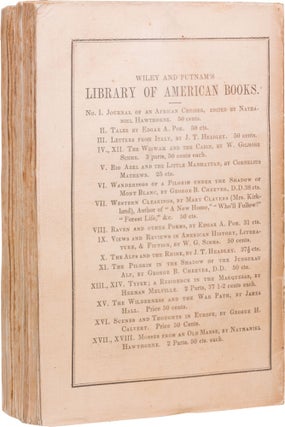

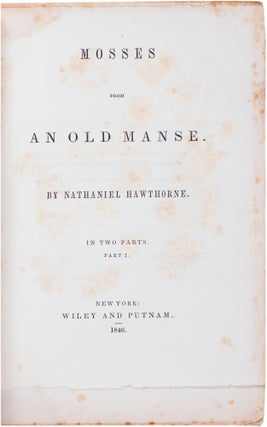

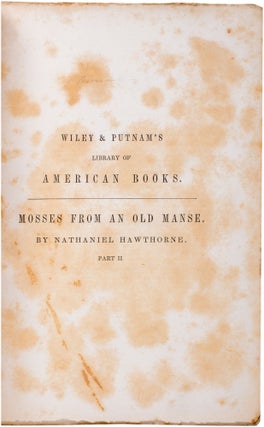

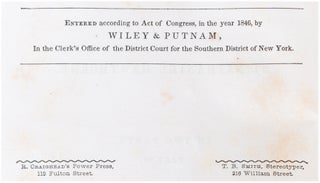

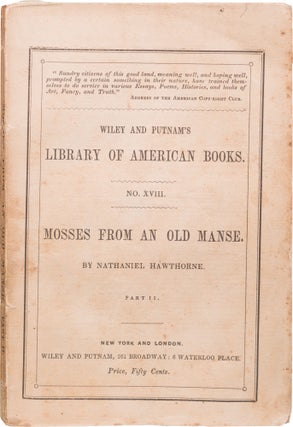

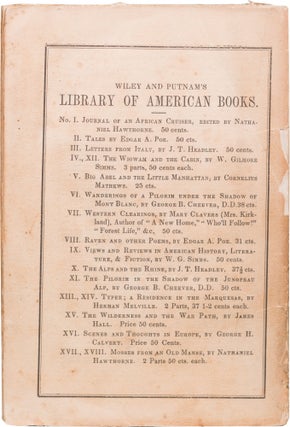

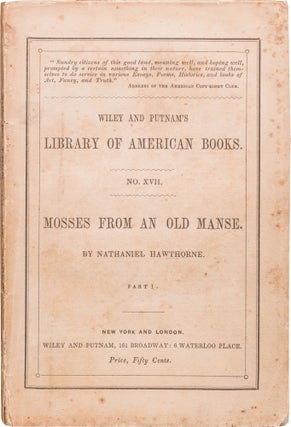

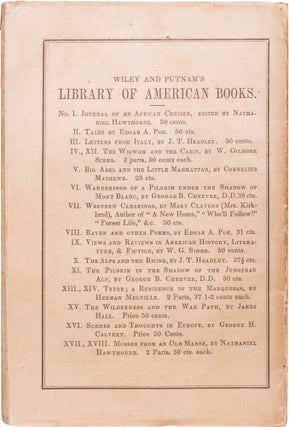

New York: Wiley & Putnam, 1846. First Edition. Wrappers. 2 vols. 1st edition of an American bequest to world literature. Original wrappers (copies in cloth are later issues and any contention that they are concurrent is wrong). 1st printing (Clark A15.1.a) with every point, 1st binding, state A of the front covers and spines, and matched backs of Wiley & Putnam ads with 18 titles listed ending with Mosses. Clark lists 5 back covers with no priority, and publishers typically first used the ads most recent to the book, and ours are therefore the tidiest, but in this case the back covers were probably issued randomly and ordering them past question is like 5 people try to divide a Kit–Kat. Small spine chips (the tips are intact), splits to 3 of the 4 joints invisibly closed (tacked back down), vol. I half–title and title short at the blank bottom (as issued), first 2 and last 2 leaves foxed (the rest clean), still, very good. A wonderful set, the nicest one known to us, of the few sets known to us (see our last paragraph below). Ex–Natalie Blair, the first great woman collector of Americana. Very good. Item #508

These 25 stories launched a new, wickeder, deeper and more literate, approach to fiction with disturbing moral and psychological implications. Here’s a taste from 5 of them. 1. Young Goodman Brown presents the reader with an allegory on the depravity of public morality and the recognition of evil, hinting at The Scarlet Letter 4 years later. The title’s namesake, a Hawthorne paradox, has an encounter in a dark forest with 17th century Salem witchcraft leaving him cynical, wary, disillusioned, and embittered of everyone around him. 2. The Birthmark is a critique on the search for perfection in which Georgiana, an idyllic beauty (and a stand–in for the reader), marries Aylmer, a brilliant scientist. She has what she believes is a good luck charm, a small red birthmark on her left cheek in the shape of a tiny hand that disappears when she blushes. But Aylmer is obsessed by it, believing it ruins her beauty. Foreshadowing infiltrates the tale, creating the horror (we know where this is going) as the deranged Aylmer’s work is consistently beset with unintended consequences, and Georgiana is wired to submit. Resolved to remove the birthmark himself, Aylmer plans the procedure, and gives her a potion he has invented to remove it while she sleeps. As she sleeps the birthmark fades away, but she awakens and dies. 3. The Celestial Railroad is another allegory, a parody of Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress, with his Evangelist replaced by Hawthorne’s Mr. Smooth–it–away, and Bunyan’s journey on foot replaced by an iron locomotive. 4. Rappaccini’s Daughter has Giovanni falling in love with Beatrice, a beautiful young woman whose father experiments with a garden of poisonous plants. Beatrice has tended the plants from childhood and become immune to their toxins, but they have contaminated her and rendered her venomous to anybody who touches her, beyond redemption by love or science. 5. A Virtuoso’s Collection, the last story, is a tour guided by The Wandering Jew through a fanciful museum housing impossible historical and mythical items, figures, books and especially beasts (the wolf that suckled Remus and Romulus, and the one that ate Little Red Riding Hood, Robinson Crusoe’s parrot, Minerva’s owl, Ulysses’ dog Argus, Eve’s serpent, and dozens more. And there are another 20 tales of equally unanticipatable imagination (especially 175 years ago!), and there is an opening sketch describing the Concord parsonage in which Hawthorne wrote them.

Mosses was rightly praised in contemporary reviews by a magic circle of Hawthorne’s peers:

“Extraordinary genius, having no rival either in America or elsewhere.”

–Edgar Allan Poe

“A wondrous symbolizing of the secret workings in men’s souls…You may be witched by his sunlight – transported by the bright gildings in the skies he builds over you; but there is the blackness of darkness beyond; and even his bright gildings but fringe and play upon the edges of thunder–clouds.” –Herman Melville

“It is unfair that his book competes with imported European books. Shall real American genius shiver with neglect while the public runs after this foreign trash?”

–Walt Whitman

But few 1846 readers were up for these kinds of stories and Mosses found few buyers, and a new edition was not called for until 1854, after Hawthorne had been validated for The Scarlet Letter (1850), The House of Seven Gables (1851), A Wonder Book (1851), and Tanglewood Tales (1853), but that is hardly shocking. In 1846, indifference was the public’s routine response to any new wave of real art, presaging America today, where not reading their own great literature is the national pastime.

What is rare? The old–time definition of a rare book was one that a specialist in that book saw once every 10 years (scarce meant once a year) and we still use that gauge here. These days too many sellers lie foolishly about rarity (and anything else they think they can get away with) but the marriage between an unreliable bookseller and an intelligent collector is always going to end in adultery. RBH shows 5 other auction sales of Mosses’ 1st printing in wrappers since 1940, and, unlike ours, not all were the 1st state throughout. McMichael’s set (Sotheby’s 1992) was defective and repaired. Bradley Martin’s (Sotheby’s 1990) was chipped and repaired. Another (at Christie’s, 1988) was crudely repaired. Gerald Slater’s (Christie’s, 1982) was fouled by black spots all over vol. II’s wrappers. And I didn’t see Paul Lemperly’s set (sold in 1940). One more set (Sotheby’s 2011), had a 2nd printing of vol. II. Our pair seems finest of all, and they are correct bibliographically, so if you fancy American literature, and want the best, for priority, condition, content, and effect, here it is, a tangible case in point that the pursuit of quality means trying to buy books that are a little better than necessary. Of course, when you don’t like the price, you can flee quality from time to time, but if you want to build a great library leave a forwarding address (Book Code).

Price: $9,000.00